Converting to 3-phase power

A practical solution for shops looking to add production machinery.

While operating cost is a definite factor, the biggest benefit of 3-phase power is smooth running motors. That’s why so many small- and medium-sized shops that are moving into CNC machinery or robotics are exploring this option. A woodworker might be able to get 3-phase hooked up to the shop by a power company or add a phase converter that changes single-phase into 3-phase power. There are other options, too.

The way 3-phase operates is that there are three AC (alternating current) circuits that are combined to deliver a single source of power. Think of electricity coming down a round cable and divide that cable in your mind into three pie segments. Each of these covers 120 degrees, or one third of the 360 degrees in a circle. The three circuits are out of sync with each other, so the power is flowing a little differently in each. And keep in mind that these are alternating current (rather than direct, or DC), so the power moves along the lines in pulses. By combining three circuits, a 3-phase system makes sure that when one wire is between pulses, the others pick up the slack. So, the stream of energy is very consistent.

Electricians would find holes in that description, but it does describe the concept.

Because there are three circuits, their combined amperage can be much higher than a single-phase circuit, so they can power bigger motors more efficiently. And a 3-phase motor is more apt to maintain rotational speed under load. That’s because it isn’t constantly catching up and jumping gaps in AC, and that saves energy. It takes quite a bit of effort to get up to speed but once there, maintaining the rate is relatively easy. The concept here is akin to pushing a flywheel or launching a spinning top. The mechanical principle is called rotational inertia, where the movement stores kinetic energy and once in equilibrium, resists change. A simple example would be that it takes more energy to roll a ball up a hill at, say, 10 mph, but once the top is reached and the ground is flat, it’s much easier to maintain that speed.

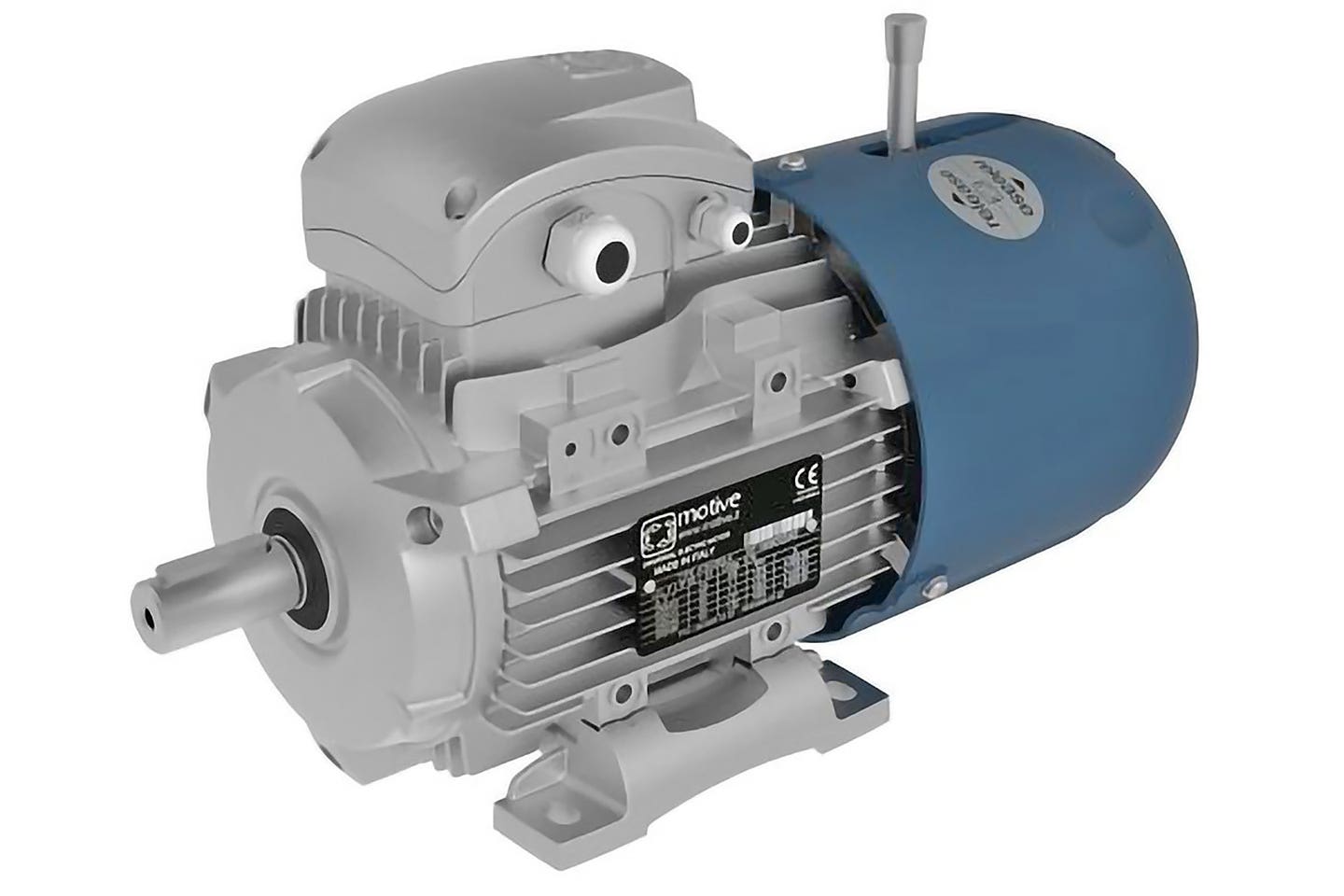

The big advantage of rotational inertia in large 3-phase motors is that they vibrate less. That smoothness lengthens the motor’s useful life, which is one reason why so many vintage machines are worth restoring. Better still, a 3-phase motor drawing the same current as a single-phase one will deliver more power per dollar. And because they don’t use a capacitor to get rolling, there are fewer parts, so they tend to fail less frequently.

The word capacitor will keep popping up in discussions about power, and there are two kinds. A start capacitor is basically a way to store energy in a device that looks a bit like a cylindrical battery, and this provides a power boost to get a motor to start rotating (pushing that ball up the hill). There are also run capacitors, which operate constantly and help the motor to run smoother by evening out the strength of the current (rolling along on the flat ground).

When to upgrade

As the amount of material being processed by a woodshop increases and the machines need to be bigger or work more, 3-phase power may be the most economical and efficient choice. There are, of course, some caveats. The voltage is much higher, so wires need to be heavily insulated and worked on by a specialist who knows how to load-balance (or tune) the system to avoid overloads. That’s necessary because 3-phase doesn’t handle overloads well, so motors need to be protected with relays and breakers. That hardware can be a bit costly, too.

So, converting to 3-phase means that machines will run more efficiently, have more torque during start-up, and cost less to power over time. But it also means higher voltage, and probably a higher initial investment.

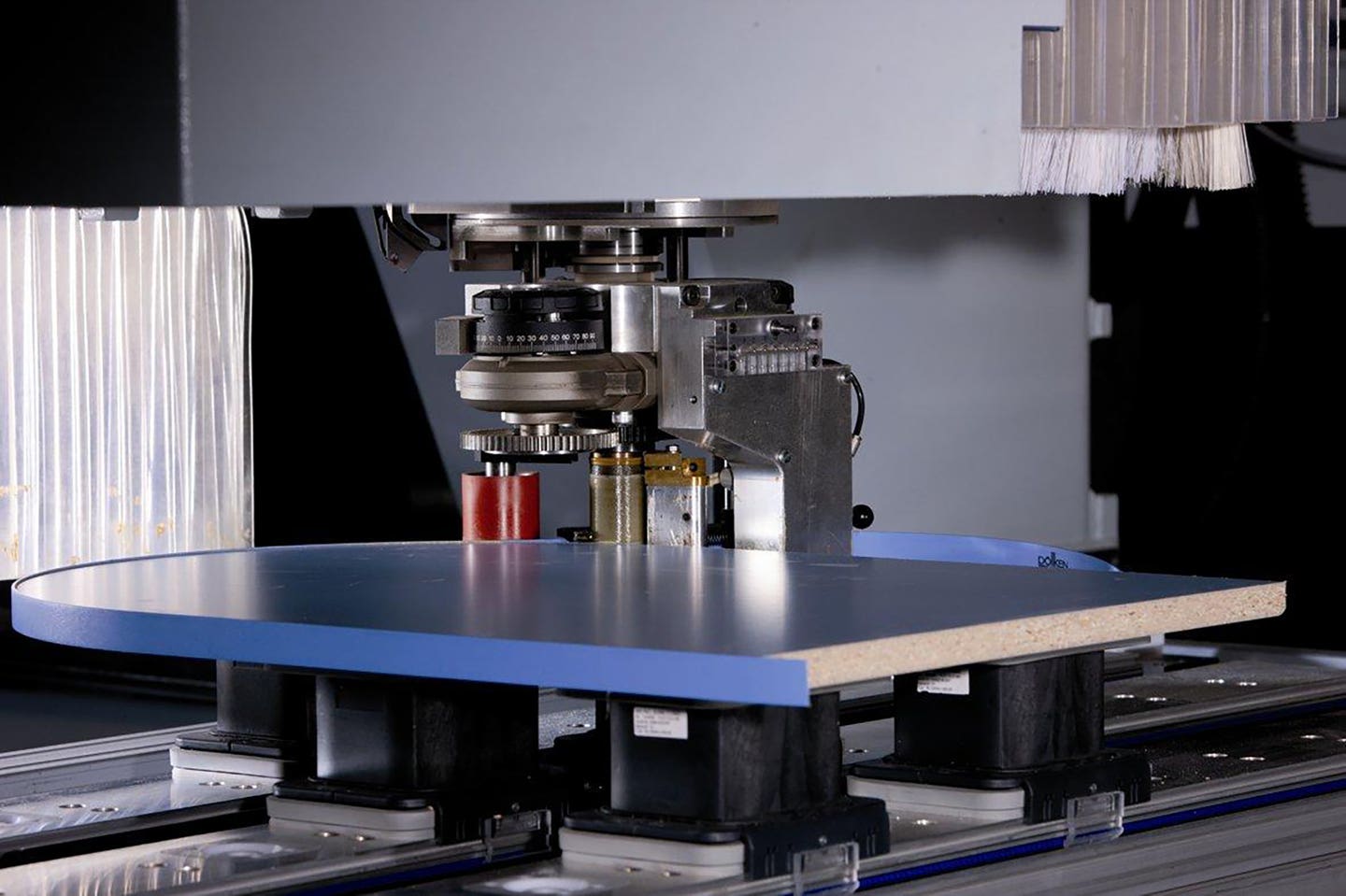

The machines that will benefit most are going to have high-draw motors. These will include vacuum pumps, central dust collection systems, large planers or jointers, table and beam saws with blades larger than 10” in diameter, wide profile molders and shapers, material handling equipment that uses vacuums, and full-sheet CNCs.

Large industrial robots usually run on 3-phase, but most cobots (smaller collaborative robotic arms that can operate safely around humans) only require 120 or 240 VAC single phase. That’s because cobots use many small motors to flex and swivel, so they tend to be primary wired for AC which is then converted to low-voltage DC inside the machine. Most machine controllers and touchscreens will also use single-phase to operate, so a 3-phase machine will almost always need a single-phase feed, too.

Phase converters

A 3-phase inverter changes DC to 3-phase AC. A 3-phase converter changes single-phase AC to 3-phase AC, and the term can also be used to describe devices that change voltage.

If the local power company can’t provide 3-phase to the building, or the cost is prohibitive, then a phase converter might be the answer. These convert standard current (usually 220 volts) to 3-phase on a smaller scale in-house, and the most common types are rotary, digital, and static.

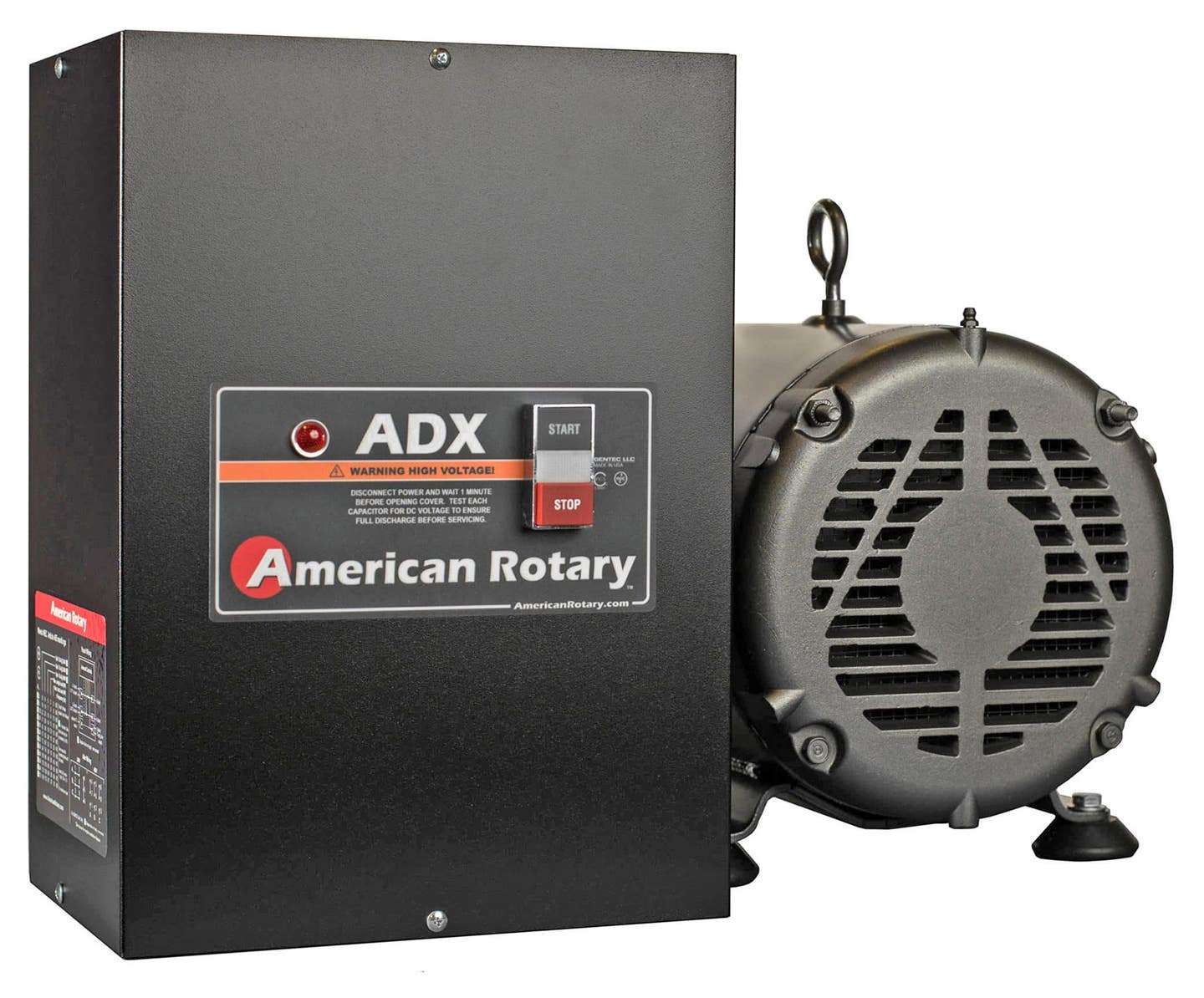

A rotary phase converter is actually a big single-phase motor that spins a 3-phase idler motor that then produces the 3-phase current. As you might think, these units are generally quite sizeable and bulky, but rotary converters can be quite reasonable to buy, install, and operate. Be aware that they can also be difficult to tune.

While small converters are dedicated to a single machine, it’s possible to run several machines on larger rotary phase converters.

A similar solution is a digital phase converter which is a more balanced and harmonious concept. Usually preferred for CNCs, a digital converter combines digital and electronic methods to control and deliver power. Not surprisingly, AI is playing an increasing role here, so expect some advances in this technology.

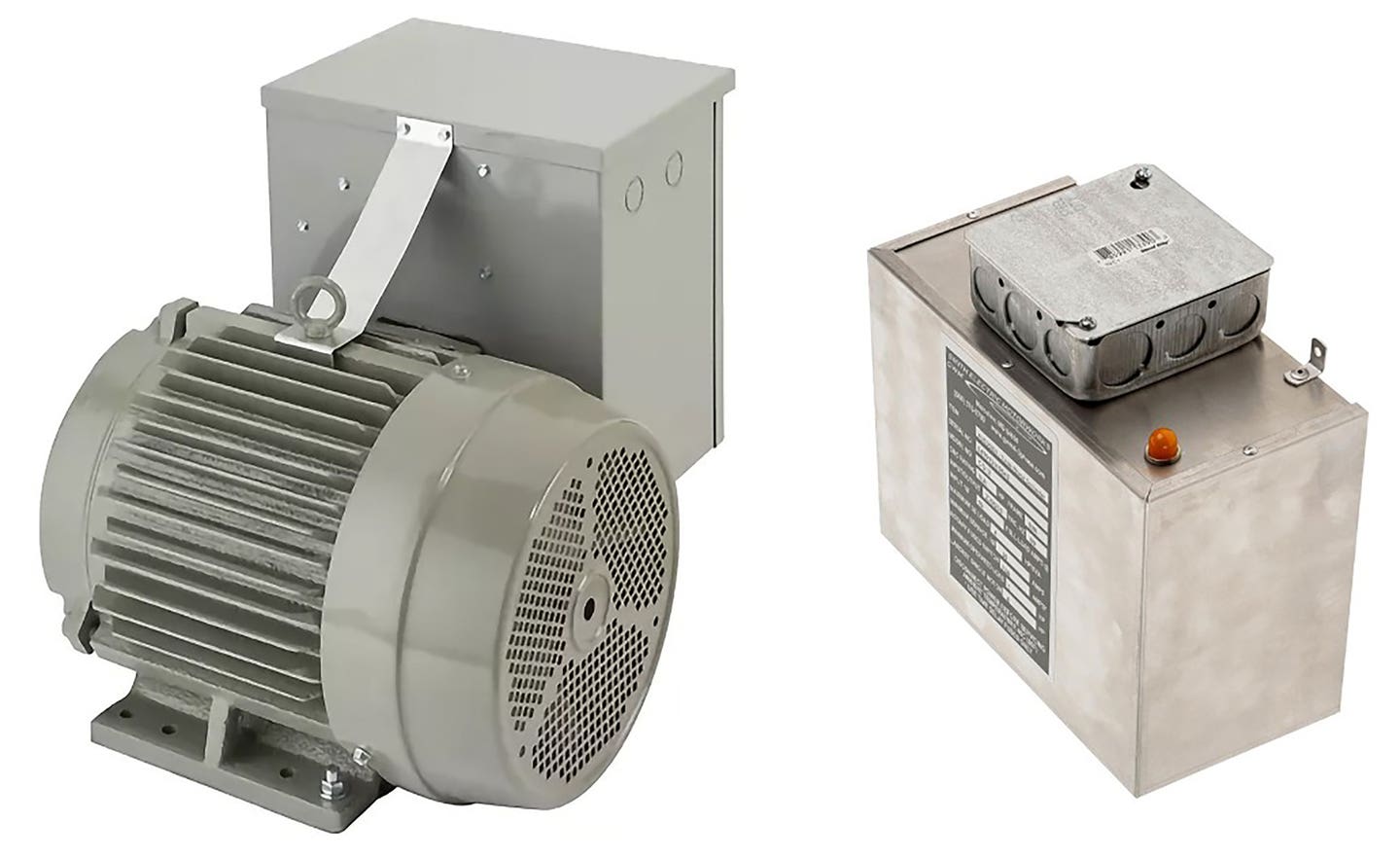

There is also an option called a static phase converter that is usually less expensive than a rotary unit. It uses capacitors to start a 3-phase motor, and it’s reserved for light work that doesn’t require the sensitivity or reliability of more expensive systems. Static converters are generally sized from about 1/4 to 10 hp and operate on 208 to 240-volt single-phase at 50 or 60 Hz. That’s the power that most of us have in our homes to run electric stoves, water heaters, and air conditioners. This can be a good solution when a small shop has two 3-phase machines and only runs one at a time. An electrician can install switches for this. Note that static devices will not operate a 460-volt motor. For this, a shop will need a rotary phase converter or a variable frequency drive (VFD) that accepts the correct voltage.

Many high-end traditional woodworking machines are now offered with smaller 3-phase motors, but the plug going into the wall is still 220-volt single-phase. There’s a small inverter right on each individual machine, and this can be an economical way to upgrade something like a lathe or thickness planer.

To size a shop-wide system, it’s necessary to do an audit of all the motors that will possibly run at the same time, and then add up their maximum horsepower. Don’t undersize it, as overloading can damage both the converter and the machine motors that it feeds.

The first thing an electrician will do when wiring in 3-phase machines is to install a separate 3-phase subpanel with the appropriate breakers or fuses and then wire this into the shop’s existing single-phase trip panel.

Unlike a rotary phase converter, static units can’t balance the load between the three circuits after the motor has started. So, a static converter never lets the machine get to its full horsepower. That’s why they’re reserved for low horsepower machines with a single motor. And they work best when a motor starts quickly. If the machine requires a long acceleration of time, a rotary phase converter is the right choice. Static units also don’t like to stop and start more than a few times an hour, and they’ll run at less than 70 percent of the motor’s nominal horsepower for extended periods.

Final thoughts

In addition to the cost of a specially trained electrician and various hardware items, some inverters and converters can be quite large and heavy. So, shipping may be a cost concern.

Some units require a fused switch instead of circuit breakers, and some manufacturers require the use of ring terminals rather than twist connectors. If your electrician doesn’t know that you might want to call another one.

The more motors that can be run from a single converter, the more the cost per motor operated is reduced.

A woodshop owner who is considering installing solar panels might want to take a second look at the shop’s single-phase machines before doing so. Solar systems generate DC power, and a 3-phase inverter converts DC to 3-phase AC. Every shop is different, so it’s worth exploring the potential there with an electrician.

Converting to 3-phase means that a small shop can upgrade to some seriously productive CNC machining centers or to large traditional machines and then run their massive motors in the most economical way.

Vintage 3-phase machines can be surprisingly affordable through online auctions, but be wary of their weight because, like larger converters, their shipping costs may be prohibitive.

On the other hand, those vintage behemoths can often handle larger parts, which reduces the number of steps in production. That can make them faster, safer, and almost always smoother than a shiny new single-phase option.

Originally published in the January 2026 issue of Woodshop News.