Total recall

There have always been lots of jigs available to help construct the two most revered woodworking joints — dovetails and mortise and tenon. Some of the better manual jigs can…

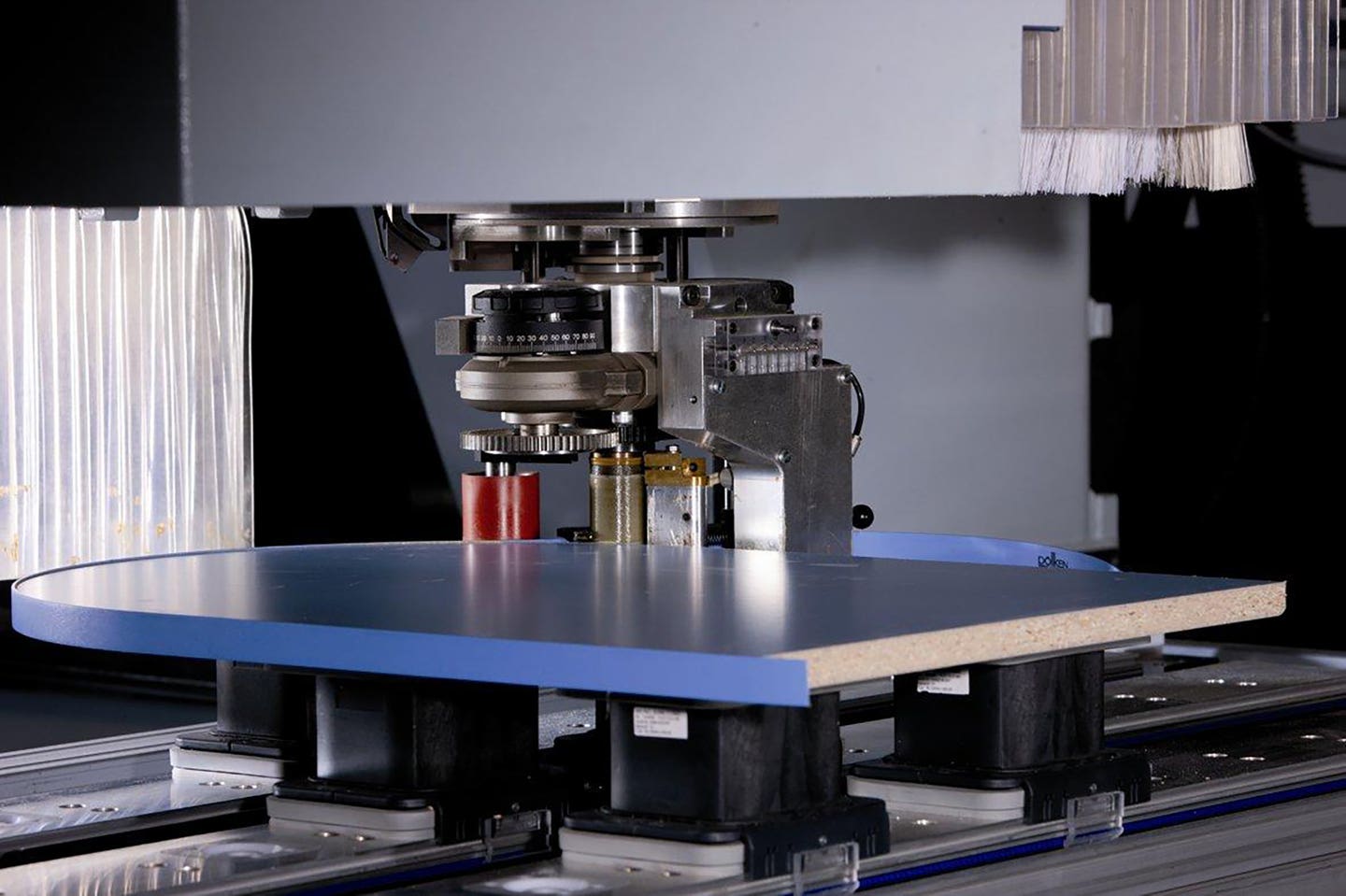

There have always been lots of jigs available to help construct the two most revered woodworking joints — dovetails and mortise and tenon. Some of the better manual jigs can get pretty expensive and those high-end ones are now running up against technology. Small CNC routing centers such as the HandiBot, Shark and Piranha Fx have made the technology much more affordable, and they can do something with which woodworkers often have a problem: they remember.

There’s hardly a cabinetmaker out there who hasn’t spent a day or two learning how to use a dovetail jig properly and then come back to it a few months later and discovered that he has completely forgotten how to set it up.

That kind of frustration is a thing of the past when it comes to CNC programs: the machine recalls the details for us. Milling dovetails for drawers is not much more complex than booting a program and locking the wood in place.

And it’s not just CNC routers that have become mainstream, but also laser cutters and 3-D printers. For less than the cost of a basic professional cabinet saw, a small woodshop can now purchase one of these machines and become a highly accurate patternmaker or jig builder. Not only can the technology help us to make parts, it can also help us design and build prototypes. Being able to print a unique part on an inexpensive machine makes a lot more sense than building half a dozen fixtures that used to allow us to execute the same part in wood.

As our fingers move farther away from cutters and blades because of automation, the need for jigs and cutting guides also diminishes. Where once a cabinet shop had an entire wall of guides for shapers and routers — for example, jigs to make curved cathedral top door rails — now we have a single USB memory stick.

While accuracy and ease of use are very attractive aspects of these newer technologies, what is really appealing to a woodshop doing any kind of production run is the machines’ repeatability. Even a small CNC can turn out identical parts all day long while the woodworker concentrates on other tasks, such as assembly and finishing. The time spent building a whole range of jigs to complete all kinds of basic shop jobs can now be spent building cabinets or even building new business. Instead of sorting through a dozen drawer hardware centering jigs, clamping them in place manually and then drilling two holes in each, one can now just program the machine to bore the bolt holes while the drawer front is being fabricated.

As jigs and cutting guides become obsolete because the tasks they once guided are being automated, the definition of “woodworker” is also being refined. Where we once knew how to use a water stone to create a micro-bevel on a fine chisel, we now know how to program a tooling path. That might not be great news for creative people who like to invent their own solutions, but it is often pretty good news for their accountants.

The joy of jigs

However, technology hasn’t completely replaced creativity. Sometimes it offers new opportunities that still allow our artisan skills and artistic aptitudes to grow. We just have to be creative in new ways.

Take, for example, the work of Matthias Wandel. For woodworkers with an engineering bent, one of the more fascinating websites out there is Woodgears.ca, which is the brainchild of this Canadian software engineer. Wandel, a master tinkerer, has come up with some amazing solutions to common woodshop tasks — some of which might just involve more work to build the jig than the labor they avoid — but they still look like an awful lot of fun. He has been doing this for a while. Thirteen years ago, he designed his own CNC precision box joint jig that is so accurate he can construct cases with fingers that are only the width of a saw blade’s thickness.

“I built this jig back in 2003,” he says. And in a counterintuitive comment on the advancement of technology, he adds: “I have since built a fancy (manual) box joint jig with a geared screw advance, which eliminates the need for a computer when doing regular box joints.” So, this leading edge engineer still feels there is at least some merit in mechanical rather than electronic controls. That tenet is also obvious in Wandel’s tilting router jig, which is also built around one of his trademark wooden gearboxes. It can reproduce complex historic moldings using just basic router bits. It will even work on curved stock to produce elliptical window and door trim. And his Pantorouter XL is a sliding platform mechanism that produces box/finger joinery, mortise-and-tenon joints and other repetitive structures. All of these are shown on his website.

In addition to highly complex jigs and cutting guides, Wandel has actually built a whole suite of traditional woodshop machinery from the ground up, including a table saw, jointer, dust collector, bandsaw, belt sander, lathe, small portable sawmill and even a hollow chisel mortiser. He doesn’t always rely on them: he also owns a number of commercial machines, which he operates in a well-organized basement woodshop in Ottawa.

Among the more interesting jigs he has designed and built is a 3-D router pantograph. Unlike most commercial versions, his pantograph also controls the router’s depth of cut by tilting the entire jig back and forth as the follower moves up and down. The pantograph, not the work, supports the router’s weight and thus the jig can precisely control the bit’s height.

Wandel offers various plans for sale, many of which include lots of excellent 3-D computer-generated drawings.

Commercial products

Woodshop suppliers such as Kreg Tools, Woodhaven, Rockler and other are constantly developing new jigs, or upgrading older versions.

Incra Precision Tools recently introduced PushGuard that combines an oversized push block with both an integrated hand guard and a removable clear debris shield. This gives a woodworker (and especially trainees) three times the safety features of conventional push blocks. It works on router tables, jointers and other machines where a traditional guard can’t be attached to the fence. The removable clear deflector shield blocks flying debris to help protect eyes as well as hands. In addition to safety benefits, this little accessory also improves workpiece control and accuracy.

Incra has also come up with a jig for reducing dust when milling grooves on the router table. Called the CleanSweep Cabinet, it’s a plastic plenum that attaches to the underside of most router tables. The vacuum that is generated inside the cabinet by a 4” dust collection hose will pull chips and fine dust downward past the router bit, keeping the table surface and the surrounding shop a lot cleaner than before. Unlike a dust port mounted on the fence, the CleanSweep cabinet works for every cut, not just when the fence is covering the router bit.

And the new Incra I-Box is a table saw and router table jig that can create a variety of box/finger joints. The I-Box is designed for standard 3/4” x 3/8” miter slots (or a version is available for Shopsmith machines), and Incra also offers options such as box joint blades, the basics for making wooden hinges, and spare backer boards. The jig easily micro-adjusts joint tightness, delivering 1/8” to 3/4” pin widths. It’s capable of making good fitting box joints using any width cutter within that range, in lumber from 1/4” to 1” thick. Plus, I-Box exclusive joints like the Center Keyed Box Joint can be used to produce symmetrical patterns on any width lumber. This means a woodworker can create joinery that matches existing project plans, rather than altering board widths to fit the limited possibilities of traditional box joint jigs.

The nicest thing about Powermatic’s latest tenoning jig, the model PM-TJ, is that it’s lightweight and easy to pop on and off the table saw. This jig was designed to eliminate the need to transfer measurements: it just uses your chisel to configure the set-up. There’s an adjustable work stop with a magnified angle gauge, so that all of us aging cabinetmakers can read it. The extruded handles are conveniently located away from the blade, and there’s built-in micro-adjustment for tenon sizing. The guide bar has set screws to eliminate slop in the miter gauge slot, and the jig can be used with a low profile riving knife.

Whether you’re surfing the websites of woodworking supply houses, gathering inspiration from engineers and jig builders or eyeing the possibility of purchasing a new portable CNC, 3-D printer or laser cutter, some of the most enjoyable hours in woodshops are spent inventing, building and using jigs and guides.

This article originally appeared in the May 2016 issue.