Making the case

The pros and cons of outsourcing, and tips for choosing a supplier

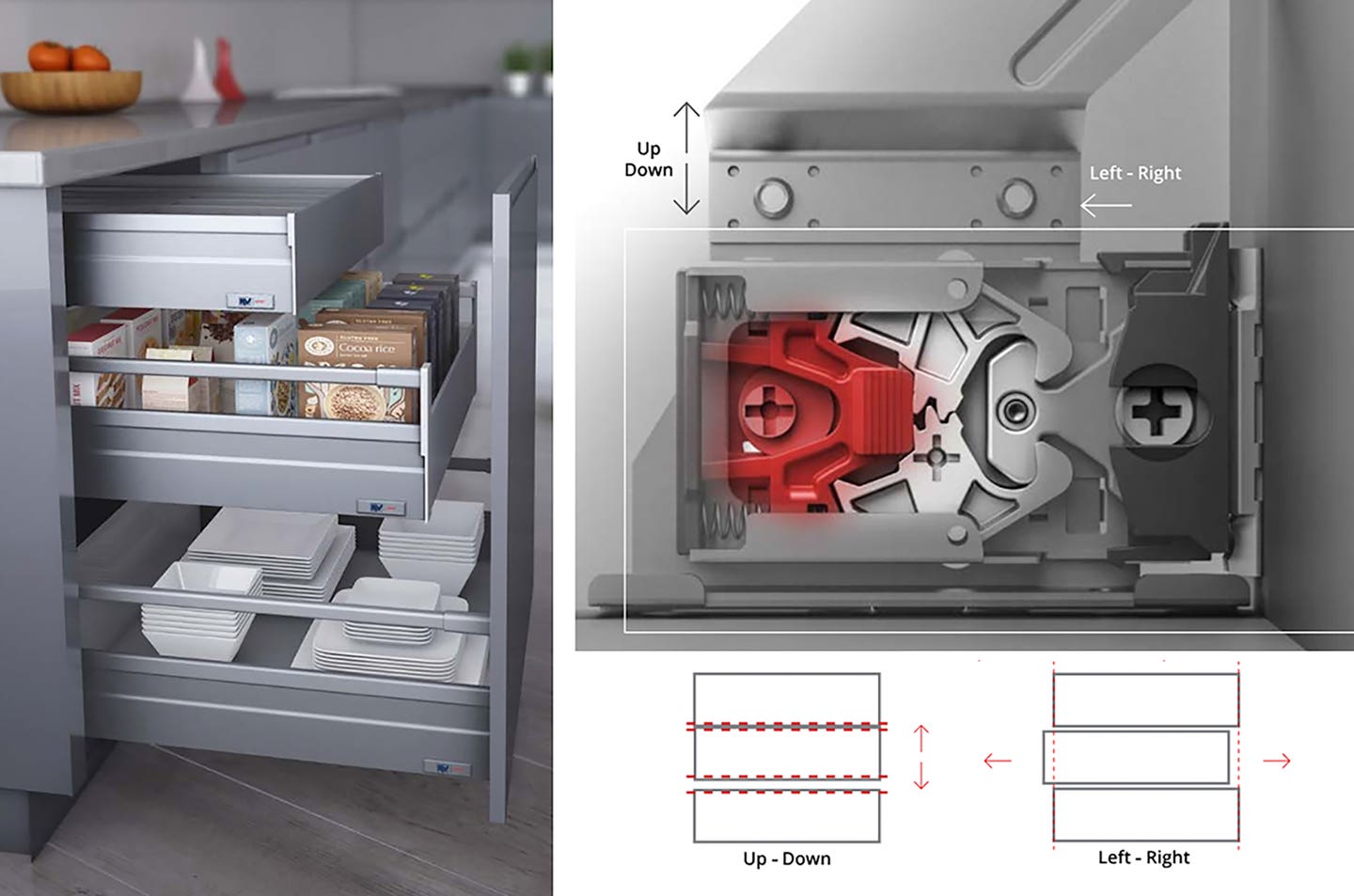

For most businesses, outsourcing means contracting out functions such as accounting or CRM (customer relations management). In the woodworking sector, it refers to buying custom parts from a large supplier. Those can include cases, drawers, doors, counters, moldings, even peripherals such as cabinet organizers and vent hoods — all of which are value-added products that shops have traditionally made in-house.

There are advantages and disadvantages to the practice. The bottom line is that the woodworker is buying something that could have been made, so its cost must leave enough margin to still be profitable. Time is money, and the number one reason that shops choose to outsource is to save time.

The advantages

Employee hours are expensive, and outsourcing lets the shop focus those hours on what it does best. If a shop’s production is centered around a CNC and building boxes, it makes sense to think about outsourcing the doors and drawers. A small shop with limited staff can only make a finite number of items, so those should be the most profitable. Often, that also means the largest items, because shipping costs are directly related to volume and weight. It’s less expensive to haul flat-packed drawers than fully assembled cabinets, so if the shop is going to retain some manufacturing in-house, it is most logical to build big assemblies such as kitchen islands.

Outsourcing is, by its very nature, a risk-sharing activity. Having experts in the field complete some tasks will reduce the risk in-house, both in terms of rejects and scheduling.

Sometimes we get stretched a little thin, and a shop that is making everything in-house can lose focus when it comes to quality. Buying parts from a company that makes nothing but drawer boxes can improve the quality of the drawers that the shop sells. Outsourcing lets a woodworker take advantage of the supplier’s expertise and specialization, without having to reproduce those values on the shop floor.

Purchasing is part of the equation, too. A 200-employee factory doesn’t pay the same for a sheet of Baltic birch as a two-man shop. Volume purchasing earns discounts.

Optimization isn’t as efficient in a small shop, as the volume of jobs doesn’t create as much opportunity to use up all those scraps and cut-offs. Even if the cost per drawer is a little higher, the small shop that outsources its boxes no longer needs to maintain an inventory of sheet stock or hardwood for drawer construction. That can free up cash, which is the engine of growth in a small business. Those savings might help finance a faster CNC or pay for robotics that in turn help reduce even more man-hours. Outsourcing also directly reduces the cabinet shop’s payroll, and the need to train and recruit, or spend time on personnel issues (because there are fewer employees). Payroll is reduced every time a dovetail jig stays on the shelf, or tooling doesn’t need to be sharpened, or someone doesn’t take a paid vacation.

From a marketing point of view, outsourcing expands the shop’s catalog, shortens turnaround times, and makes the business more competitive in the local market. It can also add new skills and products that cater to evolving trends in design and technology. It makes a woodshop more flexible, adaptable, and responsive to trends.

The disadvantages

The biggest downside is a relative loss of control. The shop owner is now depending on a third party to perform on schedule and budget, and do so with no loss in quality. But nobody in the shop knows how the outsourced job is going until it has been delivered. There’s a lot of trust involved.

Most shop owners value reliable delivery even more than price, and once they find an outsourcing supplier they trust, they are reluctant to shop around. That can be a little disadvantageous because market forces are then subserved to performance anxiety. Price is no longer the premier concern. It’s subtle, but it gives the supplier a small advantage.

There are risks involved in trusting a third party. Scheduling is probably the most apparent. Local subs such as electricians, plumbers or decorators can be flexible and may reschedule if the factory is late on a delivery, but their patience will wear thin if it becomes a habit. And the shop owner is helpless when it comes to manipulating the factory’s schedule, unless there is a rush option that comes with a surcharge.

Everything in the outsourcing relationship needs to be in writing, especially change orders. Phone conversations should always be followed by a paper trail. The woodshop is relying on somebody else’s employees, so accountability is paramount. Nothing should be done on a handshake. Once the decision to outsource is taken, those days are gone.

Another concern is that some of the largest outsourcing suppliers either produce offshore in their own factories, or else purchase products from an even larger overseas third-party supplier. And while the post-Covid supply chain debacle has been largely resolved, many of the shipping lanes still pass through politically unstable waters. Weather and weapons can cause shipping delays. Sometimes, overseas shipments are delayed while container space is waiting to be sold and filled.

There can be issues with differences in language, business practices and even time zones with offshore purchasing, so many woodshops prefer to rely on outsourcing suppliers who manufacture exclusively in North America and use natively manufactured materials.

If there is an overseas component to the relationship, one should always ask whether exchange rates will affect pricing. If possible, the currency should be U.S. dollars which fluctuate in the short term less than most other currencies, and the pricing should be locked in and guaranteed.

Other potential disadvantages are hidden costs related to packaging and shipping. If the woodshop isn’t located near a large business hub, transporting large and bulky items can generate its own set of challenges. Those can be as simple as trying to locate a suitable loading dock near the jobsite, or having truckers navigate residential or rural areas that don’t have adequate cell service or lack up-to-date mapping for apps.

These are just cautionary considerations. Most of the potential problems involved in outsourcing can be avoided by adequate planning and caution.

Choosing a supplier

Because of the custom nature of the transactions involved, any relationship between a shop and a supplier needs to be more of a partnership than the normal buyer and seller arrangement. The shop isn’t purchasing stock items off the shelf, so they usually can’t be returned for a refund. The shop’s reputation rides on the quality of products and service supplied by the factory, so diligent research in choosing a supplier is essential.

Thankfully, the online environment that lets us search for partners also helps us vet them. Search engines usually offer a set of parameters that include a rating system and a review process. Many companies provide customer reviews on their own websites, but independent opinions from the likes of Google and Yelp users are generally more reliable and uncensored.

Websites can also provide other valuable guidance. In the About Us section of a potential supplier’s site, a woodworker can usually find out how long the company has been in business and get a sense of whether it is growing or stagnant. One good clue is the number and frequency of new product offerings. If there’s something new every few months in the News section, that speaks to a business that is listening to its market. If the supplier’s website hasn’t been updated in a few years, that can be a red flag.

Part of due diligence is to ask every supplier for a list of current clients, along with permission to contact them. And then make those phone calls. It’s important to know how well your potential partner deals with bumps in the process such as special requests, shipping problems and change orders. If any of the customers exhibit an air of hesitancy on the phone, that can be a flag. And if a customer consistently excuses problems and blames them on outside factors (maybe the mill ran out of walnut), that may suggest a personal relationship that supersedes the business one. That customer may like the salesperson enough to ignore deficiencies, or at least not talk honestly about them.

If possible, visit the factory. That can be a challenge, because buying online opens a huge geographic market. So, the facility may be some distance away. But this is a crucial long-term relationship, and a walk through the plant will not only answer many questions, but it may also reveal some potential that wasn’t immediately obvious. For example, there might be a contour edge bander or a large vacuum press in use that offer capabilities beyond those listed in the marketing literature.

Things to watch for in a walk-through are the level of automation, robotics, capacities (how many CNCs or edge banders are up and running), and tooling levels, especially in terms of volume. For example, is there true 5-axis capability, or an over-reliance on aggregates?

To assess longevity and reliability, one might casually ask a few employees how long they’ve been with the company. If almost everyone is a new hire, that can be a flag.

A walk-through may also offer the opportunity to spend some time evaluating the supplier’s quality control processes. These will include both inspection and touch-up or repair procedures, and it’s important to get a good feel for what the people on the shop floor feel is acceptable, or rejectable. It may not coincide with the shop owner’s values.

It’s also important to run a credit check on a major supplier to see if there are any flags about its financial stability. Asking for bank references is a good idea too, and a call to the Better Business Bureau might be in order. (The BBB accredits more than 400,000 companies in North America.) If the supplier is a traded company, one might ask a stock analyst to have a quick look at its record.

The salient norm in choosing a vendor is to remember that you are now a customer. The outsourcer serves many shops, and while their primary interest is their own hide, their biggest customers run a strong second. Where does your shop line up? If there’s a shortage of plywood or solid wood or PUR, who gets priority? Will it be first come, first served, or will it be whomever has been buying the longest or the most?

Peripheral waves

It’s crucial to evaluate the effect of outsourcing on your shop’s internal culture before embarking on or expanding upon this option.

Will long-term employees be threatened because they feel their contribution is being undervalued, or on the other hand will they be relieved because the stress of deadlines will decline? Will they feel that they are being replaced? Will they resent being relieved of performing high-level tasks that have contributed to their sense of self-worth?

The key here is to share information with the team in real time and make the transition to outsourcing as transparent as possible. Employees are far more likely to support change that they understand than change that they question.

If some or all of the production is going to be handled by a 1099 subcontractor, where else might the shop owner look to save W-2 costs? Is there a line in the sand somewhere? In theory, a shop owner could outsource every single function except possibly sales and revert to what is essentially a sole proprietor retail business. Is the lead cabinetmaker now going to become a subcontractor for installs? With flat pack shipping, there’s no need for a delivery driver. With pre-coating, the doors on the finishing booth may never swing again.

Over time, will the custom cabinet shop become little more than a sales office for the factory? Outsourcing can augment or undermine the sense of teamwork, depending on how it is approached. Culture is important in any business, and employees often feel like a family, especially in small businesses where they have a shared history. Does a woodshop owner have a moral obligation to respect that aesthete?

On the flip side, hiring a larger shop to build components means that the shop’s crew now has access to a much larger pool of experts and professional support. That can open doors to new work, a more creative catalog, and more challenges that might keep talented employees interested and engaged. Straight lines may begin to curve, and new technologies and processes might replace mundane functions that are now being performed elsewhere. A shop might branch out from Shaker kitchens to sculpted parts for RVs and boats or delve into the world of architectural elements. A 5-axis CNC can be used to make a lot more than just nested doors.

Business owners themselves are part of the company’s culture. As such, they can craft outsourcing as a solution, a challenge, an opportunity, or even a predestined strategy.

Yes, the bottom line here is about time and money. But it can also be about growth, and new beginnings, and giving a business a makeover.

Originally published in the June 2024 issue of Woodshop News.