Identify & Eliminate

Controlling waste starts with a clear understanding of where it’s occurring.

Think about where your money goes.

In most shops, the largest expense is usually payroll. That’s generally followed by inventory, and after that probably the rent or mortgage. Then there are operating costs such as vehicles, loan payments and perhaps a lease on the CNC. The list usually wraps up with monthly expenses such as utilities and insurance.

If you’re not sure of the exact order, then you either don’t have a budget, or don’t use it as a vital tool. One can’t tackle waste until it is identified. A simple spreadsheet showing expenses for the past couple of years (grouped in categories such as the ones above) can quickly pinpoint where the money goes. Once you know that, you can start sharpening your pencil.

When a shop owner thinks about controlling waste, his/her mind naturally goes immediately to what’s going into the dumpster. But that’s probably one of the areas with the smallest potential for savings. Lean manufacturing looks at every aspect of every task and expense in the shop, not just materials, and it’s fairly ruthless when it comes to avoiding waste.

You need to be, too.

That’s because on average it takes about eight dollars in sales to add a dollar to a shop’s net profit. But it only takes one dollar in waste avoidance to achieve the same result.

Payroll options

The size of a woodshop is a determining factor when it comes to cutting payroll. If it’s a one-man shop, there really aren’t many options unless an accountant recommends a different business form (perhaps an LLC or an S Corp). But that’s usually done for liability and insurance reasons rather than taxes. A sole proprietorship may well be the most efficient form for many small shops such as furniture artists and turners. Woodworkers who are building casework that will be attached to walls probably need the liability protection of a corporate structure. But again, that’s a legal issue more than a budgetary one so it needs input from a lawyer.

Small- to medium-sized shops with several employees have a number of options available when it comes to trimming payroll. Most of them seem a little heartless, and because of that they’re often adopted as a result of attrition (somebody quits or retires) rather than dismissal. Outsourcing is the most obvious way to scale down. If a shop orders casework that is finished and delivered to the jobsite ready to assemble, that can save a whole lot of man hours. Robots are quickly becoming a close second. Robotic arms start out at about half the cost of hiring somebody for a year, and the new generation of collaborative robots are safe, efficient and extremely robust. They can handle mundane tasks such as parts movement, sorting, and even some milling/drilling and assembly tasks.

Design software has come a long way of late, and programs are much more intuitive with huge libraries and simpler cut/paste/transform options. It may be time to upgrade the CAD software and save some time (that is, payroll dollars). Many shops are also going to outsourced design, but the trick there is to find a designer who has intimate expertise in all aspects of the type of work you do (such as face frames, work in the round, specialty materials, hardware and so on). If you have to constantly retrain him/her, or suffer through costly errors, you might be creating more waste than you eradicate. Outsourcing design tasks can also invite delays, especially if the designer is in a different geographical location and must rely on the shop to visit the site every time a measurement or other piece of information is needed. Before you send out a job, find out how CAM files are going to get to your machines. Software compatibility is essential.

Inventory options

One of the primary tenets of lean manufacturing is the concept of just-in-time, which essentially boils down to ordering materials for each job as it comes online and thereby minimizing how much money is tied up in inventory. That approach often needs to be tempered by experience. It works well for easily sourced materials, but it may be necessary to warehouse some items that vary in supply, price and even quality. For example, a local mill may not always have the right species or cut available on short notice. However, a woodshop can certainly look at minimizing inventory levels on ubiquitous items such as drawer slides and MDF.

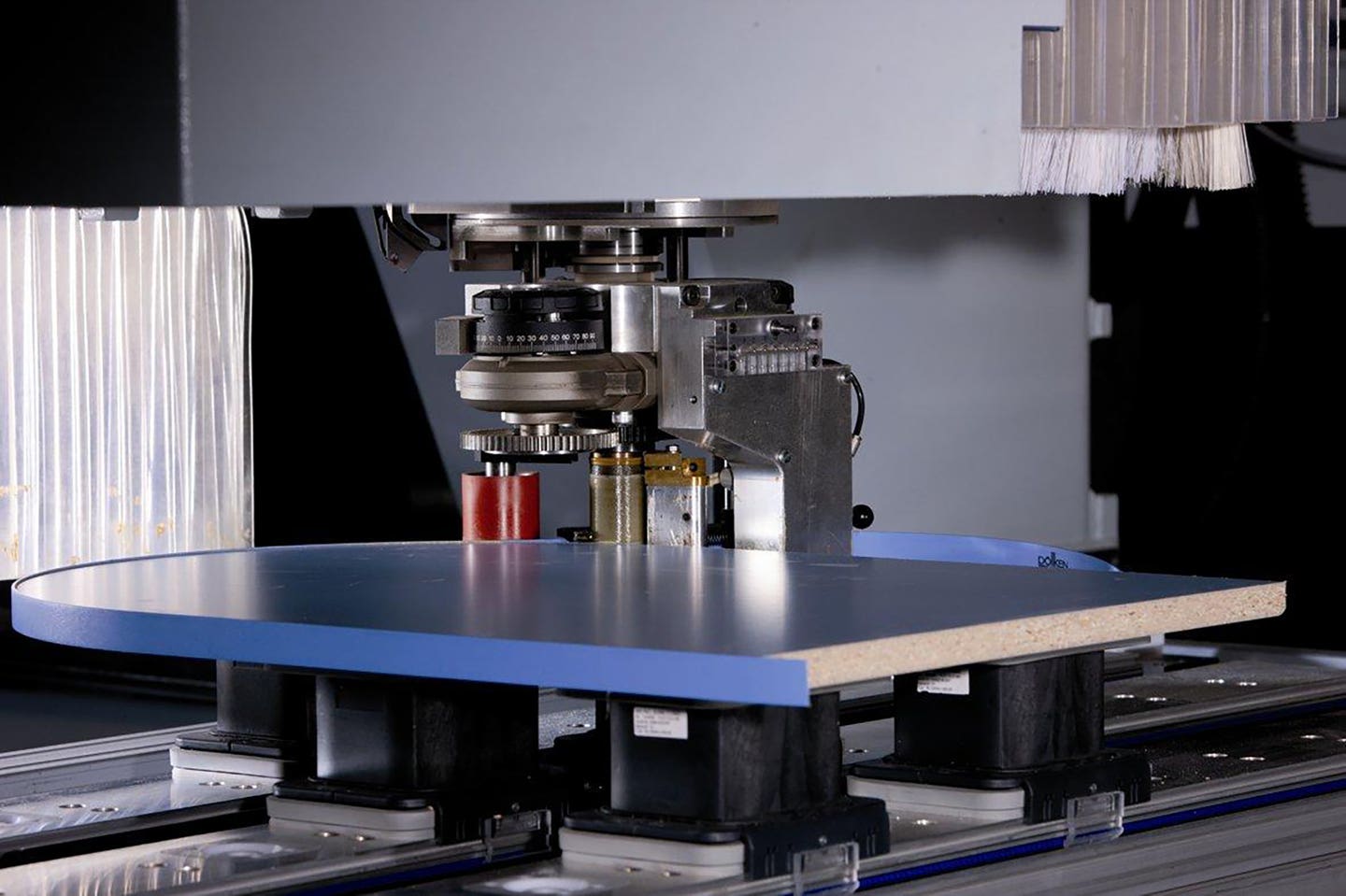

Reducing waste in parts processing usually begins with intelligent buying, and that can be informed by good optimizing software. On the shop floor, adding an automatic stop system to machines such as cross-cut or miter saws can save both time and materials, especially if the system has good repetitive features (that is, it remembers several dimensions and can automatically move to them). Adding an aggregate head to a CNC (not always an option on smaller machines) or upgrading the automatic tool changer (ATC) can dramatically reduce set-up and tool changing time.

A centralized control panel for an automated dust collection system can significantly reduce a shop’s electric bill. Central vacuum systems draw a huge amount of power to generate adequate suction, and an upgraded control system can operate the gates so that the pressure and volume requirements are always at their most efficient.

If your dust is going to the landfill, there might be a better option. Shops that work in solid woods may be able to find a market for animal bedding, composting and other landscape uses. Shops that mill sheet goods may want to locate the nearest MDF or stove pellet manufacturer, and ask if they buy. If a shop’s waste volume is even somewhat significant, it may be time to take a look at buying or leasing a briquette machine and either selling the briquettes or using them to heat the shop.

Rent/mortgage options

This may seem to be one of the least likely areas to reduce waste, but there are some solid options here. Some of them are tied to other shifts in policy. For example, a shop that begins to outsource most of its processing and some of its assembly will need a lot less square footage. That opens the possibility of subletting some space or renegotiating the lease with the landlord.

Similarly, a woodshop that adopts a just-in-time policy as part of its move toward lean manufacturing may not need as much warehouse space.

If the business has any high-interest debt and owns its premises, this may be a good time to look at refinancing. Interest rates on secured debt such as mortgages and equity loans are generally quite a bit lower than other forms of financing. Most analysts agree that rates will continue to trend upward now, so refinancing is probably going to become a little less appealing every quarter. It’s also necessary to lock in a fixed rate, and while that costs a little more initially, it is good insurance. If the bottom falls out of the economy, variable interest rates can be deadly.

Operations options

The most obvious way to reduce utility costs is to weather-seal and insulate the shop. In bad times, energy costs are the first to rise, and they often stay high for a long time. On the cusp of the last major recession, gas prices in the summer of 2008 hit a national average of $4.11 a gallon, and other fuel costs followed suit. Per calorie, natural gas looks like it will continue to be a much more economical option that electricity for the foreseeable future, so woodshops might want to take a look at how their heat system and drying/curing is fueled. Ceiling fans can make quite a difference in shops with high ceilings, and they don’t cost a lot to install or run.

The choice between buying and leasing larger equipment such as beam saws, CNC routers, forklifts and edgebanders is something that should be looked at by an accountant. Doing a detailed cost analysis involves looking at more than just the monthly payment. There are tax implications, interest rate concerns, service and support issues, even insurance questions.

For smaller shops that don’t do a lot of installs, it often makes a lot more sense to rent a delivery truck when needed rather than buying one. Renting means lower insurance costs and no maintenance expense for things such as oil changes and tires. It also eliminates a monthly lease or loan payment, and perhaps a parking space rental in some cities. This is a good subject for a detailed cost/benefit analysis, because it depends so much on variables such as miles driven and gas mileage, or subjective values such as convenience – for example, the right sized U-Haul truck may not be available on short notice.

The bottom line for woodshops is that waste control doesn’t have as much to do with what goes in the dumpster as it does what goes into the bank account. Any saving in any aspect of the business is worth pursuing, and it can be hard to see savings until all the numbers are on paper. So, when it comes to waste control, a good budget is the most important tool in the shop.

This article originally appeared in the December 2019 issue.