Here (or there) to stay

During World War II, the United States built ships in Denver. Well, OK, they built components there. The actual assembly was done 1,300 miles away at Navy yards just north…

During World War II, the United States built ships in Denver. Well, OK, they built components there. The actual assembly was done 1,300 miles away at Navy yards just north of San Francisco.

Why Denver? That’s where the equipment, skills and raw materials were located. America was in a hurry to replace both commercial and military tonnage that was being sunk in both oceans and there was no time to build new foundries and mills on the West Coast. So entire ships were loaded on trains in the Rockies in segments and transported halfway across the continent to an army of welders at the dry docks.

This was outsourcing at its finest. It’s not a new concept. Heck, half the parts on your American-made pickup truck came from outsourced suppliers in China, Mexico or Korea. That’s probably true for some of the machines on the shop floor, too.

Renting automation

Outsourcing cabinet components is almost exactly the same process as the one shipbuilders used 70 years ago. It gives a small shop the benefits of large-scale production, while still controlling the process (or at least most of it: there are a few limitations).

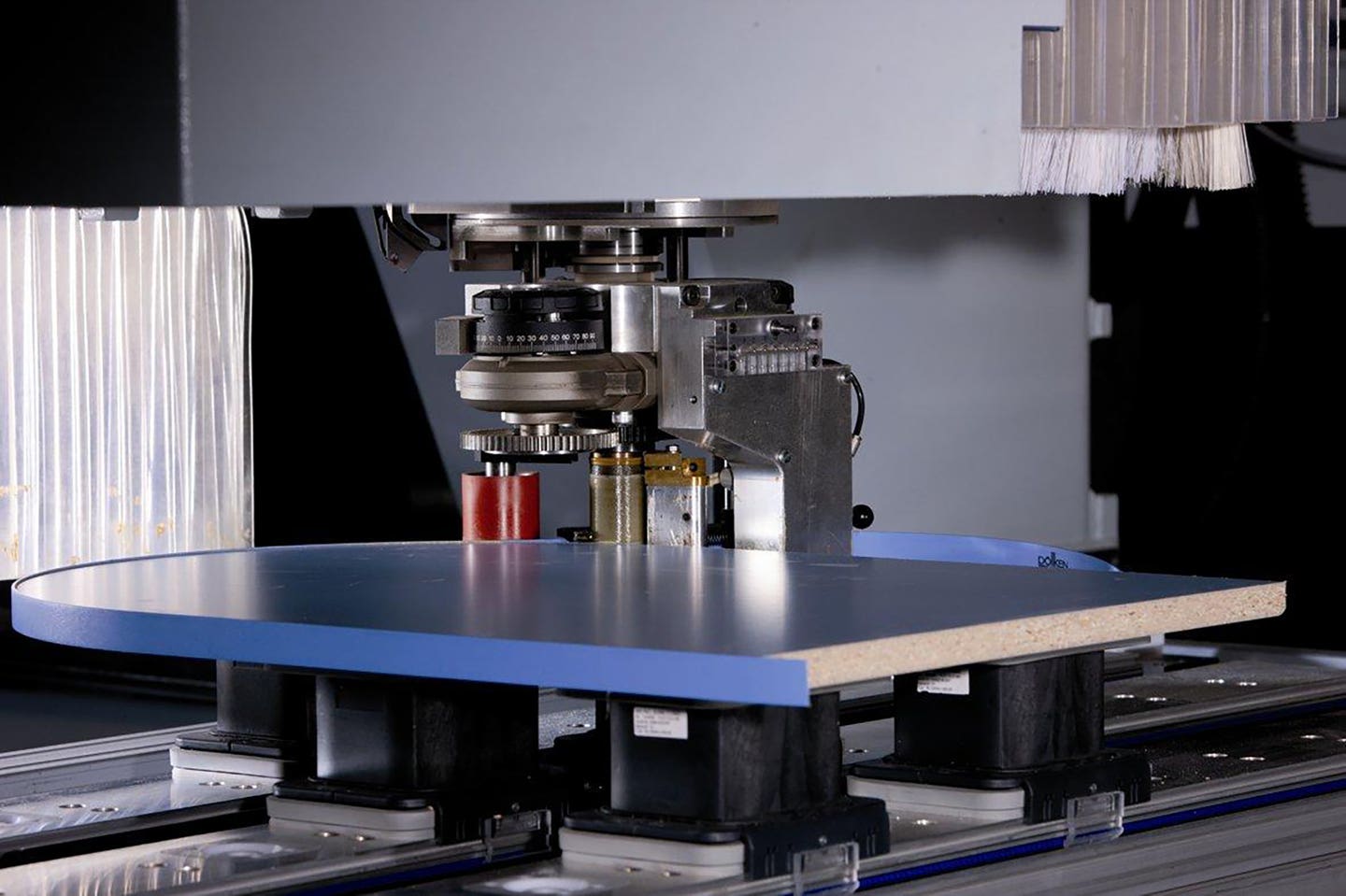

Outsourcing has become a reality because, during the last decade or two, woodworking has grown very automated. As a result, many small shops simply can’t afford the new machinery — especially large-scale CNC capabilities — they need to stay competitive. And it’s not just the monthly payment: there’s the cost of hiring or training somebody to operate both the software and the machine and even the cost of training a replacement or the shop will shut down whenever the lead man is unavailable. And there’s downtime: that payment still needs to be made when the orders are slow or the machine sits idle half the week.

The only way many small or medium-sized shops can stay at the top of the game is to automate through outsourcing — in effect, they are renting space, people and machines in a big shop that is already equipped with state-of-the-art machinery and software.

That’s not all bad. Outsourcing opens up a lot of new options. There are more door and design choices, but it’s far more empowering than that. Now a small shop anywhere in North America can offer high quality, ready-to-assemble, prefinished casework on a schedule that’s fast enough to double or triple their output. Shop owners can have a kitchen, bath or closet delivered to the woodshop or even have it go directly to the jobsite with RTA (ready to assemble) cabinets. And with solid modeling programs, a potential customer can walk through a 3-D rendering that is keyed into several of the component suppliers’ catalogs and see exactly what all those new door styles will look like in their own, personal space. Potentially, being able to carry the supplier’s catalog in a laptop means that a woodshop doesn’t even need to build a showroom.

Outsourcing has come so far that a woodshop can now order in every single aspect of a job and perform nothing more than the sales and installation functions. That’s exactly where a lot of small shops are going and it makes sense from a business point of view. More volume means higher cash flow and better profits and ordering from a catalog simplifies everything from bidding to scheduling.

Of course, if you’re in this industry because you like working with wood, the revolution might be passing you by. Outsourcing doesn’t always work for people whose favorite aspect of the business is actually building things. In the foreseeable future, a lot of smaller shops will probably change their in-house focus from cabinets to custom furniture because of that. A time is coming when custom boxes just won’t be able to compete with component suppliers whose costs are dropping as their quality continues to improve. In many markets, the role of the custom cabinet shop is going to be sales, design, project management, procurement (ordering parts), tear-out and installation. And a lot of cabinetmakers will soon be supplying entire kitchens they didn’t build and perhaps using the time they save to provide new services such as countertops, appliances, light fixtures, laminate flooring, door/drawer hardware, tile and even painting.

New marketing options

While most homeowners’ cabinet choices are loosely based on price, but in large part depend on aesthetic and emotional factors, a contractor’s litmus tests are going to be quality and reliability. That’s because a home builder who orders two or three kitchens a month needs to know that the woodshop won’t be slowing everyone else down. The ability to order and process several kitchens at a time, rather than having to build them in-house, eliminates a number of potential delays.

If, for example, a wholesaler runs out of 5/8” birch multiply or catalyzed lacquer, it’s no longer a problem. The woodshop manager also doesn’t have to worry so much about a crewmember catching the flu or taking vacations or even quitting. It takes a lot less time to train a new worker to assemble an RTA box and pop on the doors than it does to safely operate table saws and finishing equipment.

The bottom line is that construction companies almost universally view a shop switching to outsourcing as a marketing strength. Contractors aren’t really in the business of managing subs. What they do is manage large amounts of money — and time is money. So when a woodshop reduces the turnaround time for an average kitchen from two months to two weeks, that’s music to the builder’s ears.

Beyond giving a cabinetmaker the option to market a much wider variety of door styles, some outsourcing suppliers already offer plywood in several thicknesses, grades, species or finishes. This gives the woodshop the option to market a variety of price points that are based on quality. By taking a long look at the supplier’s catalog, a shop can rearrange the offerings for their particular geographic location and cater to specific demographics by offering a couple of very different budget bundles to homeowners, and a separate category to institutional customers. Repackaging the supplier’s catalog and combining it with in-house capabilities (perhaps one of the crew knows a lot about bending or turning wood) or with outsourced products from other suppliers such as moldings or hardware can allow a shop to develop its own custom marketing plan.

Become an outsourcing supplier

Not all woodshops are buying outsourced parts. Some are selling, too. And they’re not always talking about just cabinet parts.

“Our business started as a one-man shop back in 1977,” says Peter Lazar of Country Mouldings (www.countrymouldings.com) in Newbury, Ohio. “Today, building on the skills of local Amish workers, the company offers more than 800 molding profiles and a catalog of specialty items such as butcher-block countertops, solid wood flooring and stair treads. We ship to customers all over the country.”

Using locally sourced Appalachian hardwoods, Country Mouldings has developed a niche business. The company supplies products that many cabinet shops aren’t readily setup to build. The business has been successful in large part because of high quality and a stellar reputation. But part of its success is also due to the owners having the vision to see a particular need and fill it.

Country Mouldings has also evolved with the times and offers a comprehensive online price calculator. Customers can browse through products, choose a species and finish and even calculate a shipping estimate 24 hours a day.

It can be hard to find the courage to reshape a business so that it fits better in a changing industry. If a shop owner grew up building cabinets, it might even feel like betrayal to consider buying in parts of what he/she is selling as handcrafted excellence. But the reality is that life moves on and the economy becomes more automated and efficient every year. While some shops will always thrive on custom handmade artistry, many others need to move with the times.

And that isn’t always a bad thing, either. For example, a small woodshop that is set up to cut and mill parts but considers it a chore to apply finishes might be well served by approaching larger shops in the area and becoming an unfinished parts supplier. Or, turning that scenario around, perhaps the small shop has a level of expertise in finishing that would allow it to apply coatings and eliminate the saws and routers (and the dust).

Final thoughts

If a customer questions the ethics or practice of outsourcing components of their kitchen, a woodshop owner can point out that he/she has developed a strong, custom-based relationship with suppliers. Instead of the cabinetmaker’s crew building parts in the local shop, his “other” crew is building them at a better price and some of those savings (especially in terms of time) are being passed along to the customer.

When times are slow, shops that outsource aren’t sitting on thousands of dollars worth of sheet goods, hardwoods and other inventory. Outsourcing is, in effect, a way to practice lean manufacturing. You only buy what you sell and it’s done on a very timely basis. There is virtually no waste.

Oh, and one other big advantage to outsourcing is this: the woodshop is a whole lot easier to clean up after every job.

This article originally appeared in the May 2015 issue.