Building the stairway to heaven

The traditional stair market is dead. At least it is as far as Fred Loucks, Brian Gulick and Dan Hill are concerned. The three partners in Salmon Falls Woodworks LLC…

The traditional stair market is dead. At least it is as far as Fred Loucks, Brian Gulick and Dan Hill are concerned. The three partners in Salmon Falls Woodworks LLC in Dover, N.H., want no part of the mass staircase market as it has evolved.

Building staircases from pre-cut, essentially cookie-cutter parts isn’t for them, although they’re glad to make the parts for other woodworking companies.

“Assembling pre-manufactured parts is not the market we want to be in,” says Gulick.

So the partners go after more exotic jobs. They specialize in nothing and leave themselves open for anything. That may mean the conical-shaped closet in a Manhattan apartment they’re just finishing. Or it may mean building a Japanese teahouse on top of a SoHo apartment.

“We see ourselves as problem solvers,” says Loucks.

So when it comes to stairs, the problem must be as big as the budget.

If they’re not building a stairway to heaven, the job should at least require a crane for installation and carry a seven-figure price tag.

Challenged by design

Of course, such jobs don’t come along every day. So they build only one to two staircases a year. The stairs are simply part of a “problem solution” mix for their six-person shop. That mix also includes more mundane contract manufacturing for other local shops. Salmon Falls makes furniture, cabinets, staircase parts — including handrails — signs and molding. Roughly 25 percent of the company’s work comes from cabinetry, 25 percent from furniture and the other 50 percent from millwork.

Contract work, like the bed order they landed at a recent International Contemporary Furniture Fair, allows the three partners to keep the doors open and keeps them adept at handling multiple types of woodworking jobs — keeping skills sharp for the million-dollar staircases and Japanese tea houses set upon SoHo roofs.

Though the partners have been in business together for three years, their combined woodworking experience totals about 50 years.

Gulick and Loucks worked together for 12 years before Salmon Falls. Hill officially joined the team after a stint as a woodshop technician at the University of New Hampshire. Prior to forming their partnership, the trio often cooperated on various jobs. All three have furniture backgrounds, and the desire for design challenge underpins the reason Salmon Falls exists.

The aggregate experience and contacts gives Salmon Falls access to those top-end, “problem-solving” jobs.

New digs

That combination of high-design capability and the more mundane contract work has proved successful.

The partners just moved into a new 7,500-sq.-ft. shop down the street from the mill they had occupied. And they plan to add two to three employees in the next few months, including a skilled woodworker.

Salmon Falls relocated because of the increased need for efficient materials handling. The old shop was split into two sections, 300 feet apart. With more contract work coming in for everything from cabinet boxes to molding runs, the split created a tremendous time-waster. The partners found they were wasting at least 15 hours a week just walking back and forth between the two parts of the shop.

“Just taking out the wood dust was a about a five- or six-step process,” says Hill.

CNC capability

The split between buying used machinery and new woodworking technology tends to fall along efficiencies and precision the new equipment creates against the work the old machinery does for far less investment.

"We have a new router and sander," says Gulick. "The sander allows greater precision and is really worth it. With planers and jointers, they are inexpensive and the technology hasn't changed all that much."

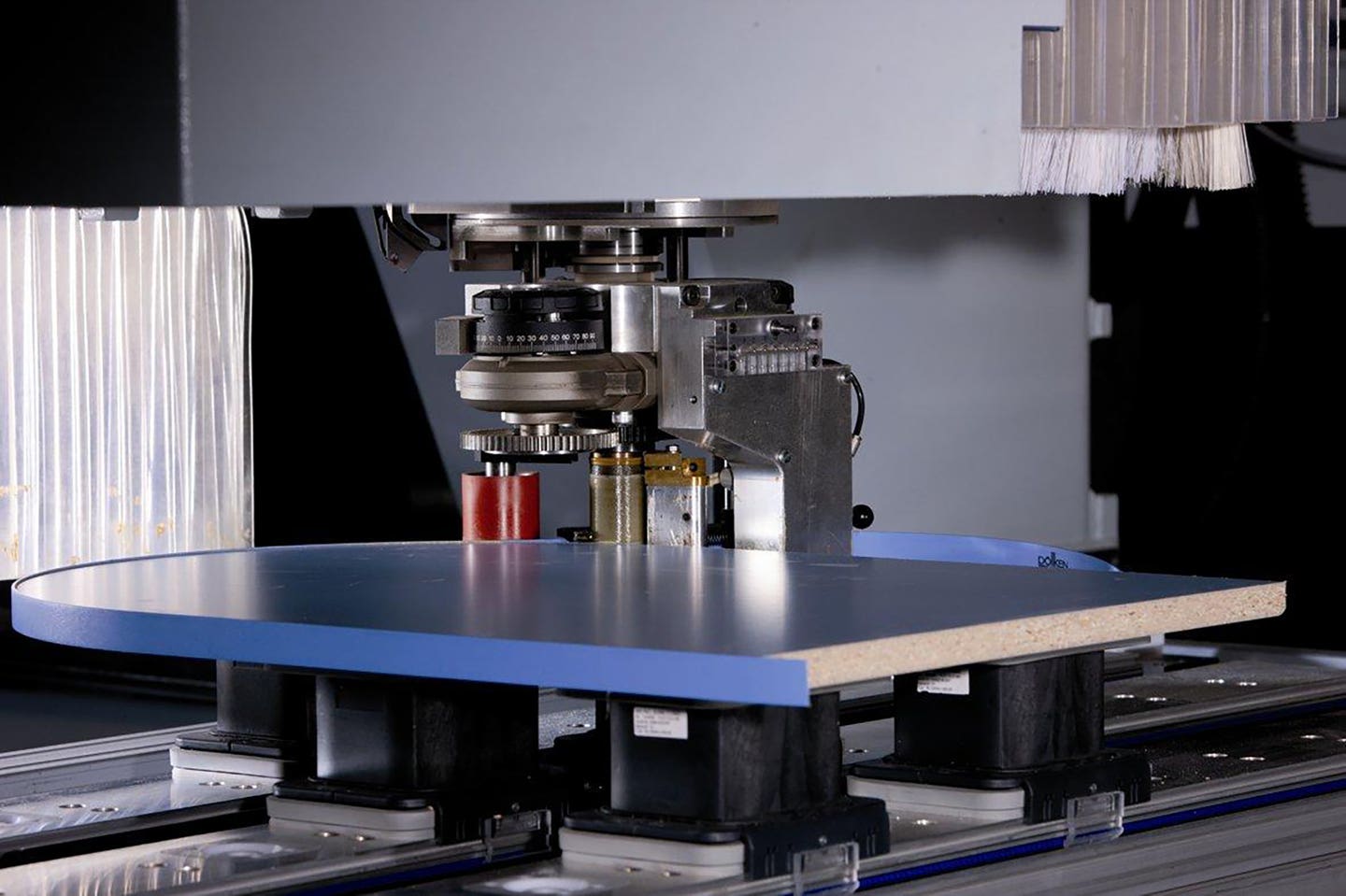

So Salmon Falls has a Whitney planer circa late 1930s and a Crescent chisel mortiser and Porter planer from the 1950s. Alongside those dinosaurs stands an SCMI sander and a CNC Multicam router they purchased through Damon Automation, a nearby machine dealer.

Coupled with a new software program Hill is learning, Enroute-Pro 3, the router allows Salmon Falls the option of performing standard routing, primarily on an X-Y axis. They use the router for the signs the company makes. However, the new software allows for much more complex, three-dimensional work not usually associated with standard CNC routing. The software allows for carving much more intricate details that engage the Z axis much more than previous software allows.

As a result, the router performs tasks more associated with hand-carved details than with CNC routing. It also allows the company to fabricate 3-D, MDF forms for complex jobs like the conical closet.

For that job, Salmon Falls used the router to shape the forms. They made the entire closet cone in multiple sections and then assembled them. They laminated the panels around the form using a vacuum press. They then put the laminate and the form back on the router and used a three-dimensional tool path to cut out the laminate panel from the form.

"I don't know if we would have even been able to do it all without the router," says Hill. "The router also made it repeatable. And all the pieces fit together perfectly," he says. "Cones are very tricky when you break them up and try to put them back together. Angles change and things change."

In all, Salmon Falls made the closet from 10 sections that all had to fit together.

They also use the router for more traditional woodworking jobs.

"We're doing all the carved panel details for a library on the router," says Hill.

The trio doesn't see modernization as a step away from woodworking. They see it as a way to attract and complete the kind of challenging jobs that test their woodworking skills and experience, and expand their knowledge.

Glass, metal and wood

A seven-figure staircase (see photo, page 35), fabricated for a Manhattan apartment, is a prime example of the work the three really enjoy.

The staircase cantilevers out from a 21' glass, stainless steel and aluminum wall in a gentle curve. The cantilever gives the impression the staircase floats, independent of support. In reality, Hill, Gulick and Loucks had to work closely with a metal fabricator, Tripyramid Structures. Tripyramid made the wall with glass panels sliding down vertically between the stainless steel and aluminum ribs. Two stainless steel faces sandwich an aluminum core.

On the other side of the wall supporting the staircase stands a second glass wall that echoes the staircase wall, essentially creating a double wall.Salmon Falls anchored the staircase, tread by tread, into the metal frames.

"We had to decide whether or not to do solid wood or laminated treads," says Wyberg. "We went with the laminated. It was stronger and, the way the metal was inserted, it needed to be robust. In one corner tab, going up the stairs in the upper right corner, a threaded bolt was epoxied in place and a series of vertical, threaded bolts the treads press down on were then epoxied into place."

Salmon Falls also crafted a 40' cherry handrail to soften the structure, which curves up the staircase and into a hallway, and added leather insets to the treads. The completed staircase has earned rave reviews, both for its ingenuity and execution.

"I've worked with Fred and Brian and have a history with them, and I knew the quality of their work," says Katharine Wyberg, of James Carpenter Design Associates Inc. inNew York City , who designed the elaborate staircase. "Typically, we work with light and glass in creating a space. The clients approached us to put something in their home knowing we work with glass. So we hung a glass wall from the ceiling. The vertical ribs come down and each carries a tread, in between the ribs there's a glass membrane to strengthen the whole system. Behind is a diffuse glass wall."

The quarter-sawn white oak treads and the cherry handrail pick up wood accents elsewhere in the home.

The handrail, which sweeps upward, following the stairs' curve and then across an upstairs hallway open to the foyer below, carries a traditional, functional, safety responsibility, but it also shoulders an important design responsibility: It unites the metal and wood and gives the staircase a coherent flow up the stairs and across the hall.

Thus, the corner at which the handrail joins with the foyer railing stands as the nexus point for the entire project — the right transition and the whole designs flows and works as united piece of functional sculpture and the wrong transition and the whole piece becomes disjointed and separated.

"They did samples and mockups of the handrail and also of the stair treads," says Wyberg. That's a key to executing the design, she says. "The elliptical shape was at an angle and we had several options on how that corner could be, where the handrail meets the guard rail at the top of the stairs. That corner is a weak corner and it would have to be sculpted as well. That was important. We wanted to see if we should accentuate the joint or continue the sweep."

For Salmon Falls, complex work like this results from years of business connections and from the work that comes through the shop every day.

"Certainly we have to do one type of project to do the more complex pieces, but you can apply the same problem-solving ideas to all the jobs," says Hill. "They relate to each other and you have to do both. It's a cumulative process, this whole woodworking business."

Contact: Salmon Falls Woodworks Dover, NH, Tel: 603-740-6060. www.salmonfallswoodworks.com