A world of wonders

The multifaceted Paul Schürch, owner of Schürch Woodwork in Santa Barbara, Calif., has an impressive repertoire of more than 250 unique pieces influenced by classical styles, sometimes with a twist….

The multifaceted Paul Schürch, owner of Schürch Woodwork in Santa Barbara, Calif., has an impressive repertoire of more than 250 unique pieces influenced by classical styles, sometimes with a twist. And Schürch is as dynamic as his work. With more than 30 years of woodworking and other diverse trade experiences, he draws upon this knowledge to create unique limited-edition and one-of-a-kind pieces. He speaks several languages, travels often, and continues to network with other masters, craftsmen and students around the world.

Schürch’s work is mostly known by his loyal following of private clients, gallery owners and designers for his furniture work, with the attention to detail and intricate marquetry with playful imagery layered into the classical influences he has been exposed to throughout his career. He occasionally complements the veneer work with decorative shell, stone and metal inlays. The results are anything but assembly-line furniture, and they usually end up as a ‘stand-alone’ as the focal piece for a room.

Nowadays, Schürch is relying on the continued success of his classes on furniture making, veneering and marquetry techniques to pass on the knowledge he learned in the past. Aside from teaching week-long seminars at his own studio and places such as the Marc Adams School of Woodworking in Franklin, Ind.; William NG School of Fine Woodworking in Anaheim, Calif.; Little Gum Creek Workshop in Atlanta and AWFS in Las Vegas, he is becoming more involved in modern technology to increase the interactive flow of education. He’s also becoming increasingly involved with designing and consulting for other woodworking shops and interior designers.

“There seems to be a great need to retain and revitalize some of these hand skills that are becoming lost in today’s modern shop environment. I am grateful that I have a role in supporting others to achieve their desire to become more versatile and skilled in the woodworking trades.”

European influence

Schürch grew up in Santa Barbara and leaned to play the piano when he was 5. He entered the National Guild of Classical Music, which he attributes to wiring his brain in a certain way allowing him to multi-task and think outside the box. Before he was finished with high school, his family moved to Bern, Switzerland, where his father, an astrophysicist, was born.

“I wasn’t really inspired by the American school system, and my parents wisely decided that I should pursue a trade instead of following a scholastic career.”

Overseas, he learned the languages of Swiss German, French and Italian. He had considered becoming a professional musician, but seemed happiest building with his hands. Schürch began his apprenticeship building pianos at the Wernli Klavier Fabrik in Bern for one year. Then he transferred his studies to the Neidhart und Loete Orgel Fabric in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, where he worked with several trade masters engaged in the art of designing, building and finishing mechanical tracker pipe organs for churches and private residence throughout Europe. He graduated with honors with his journeyman’s degree in 1978.

After graduation, he worked as a journeyman for the Gumilgen Orgel Fabrik in Switzerland through 1976. Still in his early 20s, Schürch had no definite career plan set, but wanted to continue training in the things he admired and enjoyed doing. It seems as if he found his calling through a bizarre combination of different skills and, as he jokingly says, “What happens when you combine a church organ builder with a boatbuilder? A marquetarian, of course!”

Returning to Santa Barbara, he worked for a local shop for a year, building cabinets. Then he decided he had to break out on his own, to find a niche that would challenge him, and exercise his artistic skills in a new way.

Can-do approach

Schürch started working out of his garage in 1979 with a few hand planes, a refurbished 10" Craftsman table saw, his beloved chisels and a strong desire to succeed.

What sets Schürch apart is he relies upon various forms of income to sustain his small business, especially in this difficult economy. Teaching, writing, tutoring, product sourcing and testing, consulting, and selling veneering tools, all supplement his furniture making, which still remains his primary passion.

When he initially started his own shop, he centered on the local economy and relied on his clients’ word-of-mouth to get work. He took anything he could get, most of it being some kind of specialty work, including circular stairways, millwork and cabinets in curved kitchens.

“It was challenging, to be sure. I got the jobs no one else wanted or knew how to do. My first response was to say to the client ‘Sure, I can do that.’ I seemed to be up for the challenge and would convince the client that I somehow knew what I was doing.

“Clientele that appreciated my work started growing and I started displaying my stuff in galleries with an eye toward museum shows. It’s a gradual process that takes patience, perseverance and a lot of hard work.”

Schürch solicited himself to builders, designers and architects, went to new building sites and dropped his card into designers’ hands wherever he could. Hanging doors or doing carpentry was a way to get on the job site, and, soon after, clients began to notice he had more skills that could be utilized for more complicated work. It was a gradual process that allowed him to slowly put money into good tools and set up a shop to do what he really wanted to do. Later, as his shop grew, he relied upon many apprentices, co-workers and specialty shops to help complete the projects he had.

“I have great gratitude for the efforts of these people that helped me get to where I am today.”

Traveling woodworker

Still, traveling was a big part of his life. With schooling and scheduling work, he has to make travel plans about eight months to a year in advance. He has traveled back to Europe at least once a year to visit family and friends and to continue his education from the masters. Joseph Neidhard in Switzerland and Franco Remonti in Italy are two that have influenced him very much.

“I still feel so humbled by the craftsmanship I see in Europe. They really know how to put stuff together. Unfortunately, they also suffer from modern times, where cheaper products are more readily available, and more and more shops close doors, not being able to attract the younger apprentices to learn from and replace the retiring masters.”

Schürch realized he had gaps in his knowledge, needed more education, and wanted to see more of the world. He traveled for one-and-a-half years around the world, woodworking in shops in New Zealand, Japan, Egypt and England. He discovered he didn’t really understand curves very well —how and where to apply them — and knew he could possibly find what he was looking for in the boatbuilding environment. Anyone can build a box, but he wanted something more.

Schürch went to the International Boat Building Training Center in Lowestoft, England, and completed a nine-month course. Lofting a boat was something new and helped develop his intuition and understanding of the ‘faire curve’ and building the rounded shapes used in curvilinear projects.

“Boats have no straight lines, and the only reference point is an imaginary waterline. Now that sounds interesting. It is in the well-faired curve where magic happens.”

In 1986, he worked as shipwright aboard the 150' topsail schooner, Star Pilot, while on a delivery run to the Parade of Tall Ships in New York. His duties included overseeing all woodwork aboard the 70-year-old Gloucester fishing schooner, rebuilding the galley, maintaining the hull, deck and rigging, and training two young ‘chippys’ as boatbuilders.

After the ship’s journey, he went to Florence, Italy, and was stunned by the beauty of the inlay work he saw in the museums. This changed his life forever. He discovered marquetry and also Pietra Dure, which is marquetry using semiprecious stone. He went back to Florence in 1987 and worked with a Pietra Dure master for a short time.

Broad clientele

Schürch’s clients are usually wealthy and cultured individuals. They want a focal piece for their home and appreciate the artwork and quality of craftsmanship involved.

“You have to use the best material available, and you should put the best craftsmanship that you are capable of first. Utilize technology if you have it, but always stand behind your work, no matter what.”

While he has taken on commercial projects in the past, such as church, temple or corporate clients, those jobs have been less common and now only make up 15 to 20 percent of his work. About 10 percent of his clients are from Santa Barbara, another 70 percent are from throughout the U.S. and Canada, and the rest are overseas.

With new clients, Schürch uses his Web site to display various ideas. He will discuss a design with a potential client and draw thumbnail sketches, for a set fee ranging from $200 to $1,200, depending on the scope of a project and intricacy of the preparation, which could involve extensive research or a site visit across the country.

A working deposit is taken after the design phase is complete and the client is responsible for full payment and any additional delivery costs at the time of the project’s completion. Schürch spends three months to a year on most projects.

Schurch has built custom projects for many designers and currently has spec work displayed in the Northwest Fine Woodworking Gallery in Seattle, Wexler Gallery in Baltimore, and Once a Tree gallery in Los Angeles.

Inspired by nature

Marquetry was the medium that allowed him to express his artistic imagery with woodwork. Schürch trained with Remonti Intarsiatori in Treviglio, Italy, in the advanced art of inlay techniques and marquetry for six months in 1989. It was the foundation he needed to follow his passion

“I’ve seemed to settle into this technique of inlay, because it seems to suit my needs of expressing myself artistically through the right side of the brain … on the left side of the brain, I create blueprints and do the mechanical design work.”

One can’t help but notice Schürch’s work looks meticulously engineered. A graceful curve or a small detail here or there. But contrary to how it appears, the inlay and marquetry is not as difficult as building the furniture piece itself. He will spend up to 20 percent of the time designing and drawing the blueprint of a piece prior to cutting wood.

“I break my stuff down into three styles that can appeal to different groups of people. One is the neoclassical-oriented design rooted in tradition. Bouquets of flowers, ribbons with swags. They go to clients that have a classical eye that like the left hook I throw into it. Another is an Oriental style of simple lines and images, and the style of Art Nuevo, organic, floral and flowing in nature. These styles are now tending to merge together in the designs I presently do.

“I feel that the furniture has to have a common theme between the imagery and overall shape to really be successful. Too often I have seen furniture with an overall design and imagery that seem to be done by two different shops or designers, which was often historically the case. I want them to work together, to project a unified visual feeling.”

Schürch moved into his present 3,300-sq.-ft. shop in 2001. “Santa Barbara is a small, beautiful beach town with lots to offer. The downside is the high cost of living and the premium on shop space. Thankfully, I was lucky in finding the right space when the market was relatively low.”

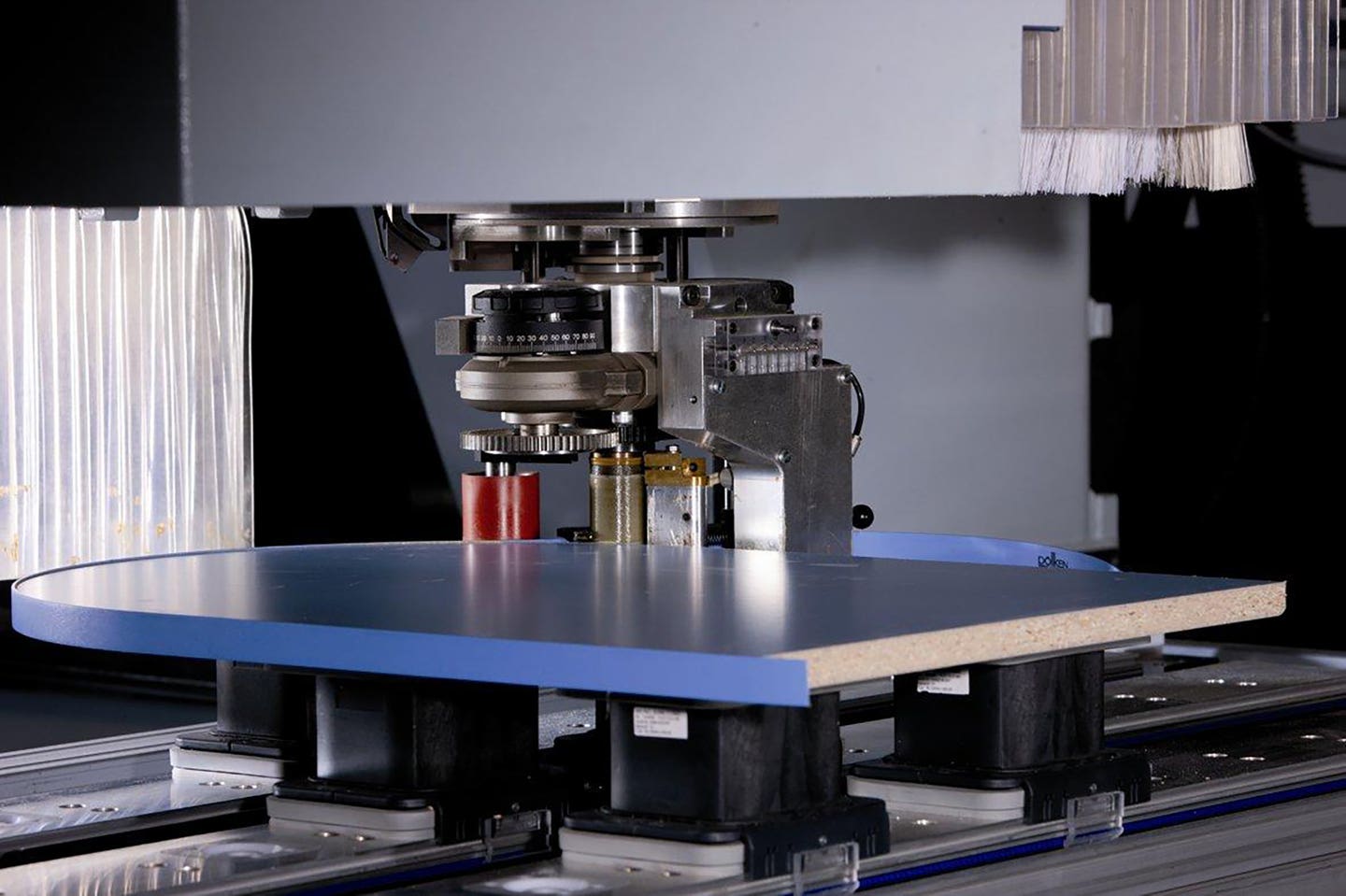

The shop features a Powermatic 10" table saw, Walker-Turner lathe, Kirchfeld 4' x 8' hot press, Vac-U-Clamp vacuum frame press, and several Festool tools. He shares the shop with another cabinetmaker and has access to a Martin table saw and Delta 12" jointer. The many European hand planes, saws, and veneering tools are used on a daily basis.

Schürch employs a full-time apprentice and bookkeeper, and subcontracts most of the shop’s finishing work because of an intolerance for certain solvents. He also subcontracts some of the metal work and all of his Web site development.

Turning to teaching

Schürch says he would love to continue building large furniture pieces, but it’s becoming a question of priorities and how much his body can take. He is now doing smaller projects such as jewelry boxes and smaller pieces. The table he is currently working on is a small 30" diameter inlaid sushi table with an expanding flower pedal drawer mechanic, which will open all curved drawers simultaneously by spinning the top on its center.

He is also teaching furniture making and marquetry classes at his shop, which he started in 1999. The teaching occupies about 30 percent of his time these days, as he usually teaches about eight classes a year. He also schedules individual tutoring for those who need assistance.

“Some people don’t have time to come out and take a class. They’re so busy with their lives and work that I can come out to their shop and set them up with what they need”.

In the case of larger shops, he has been hired as a consultant to look for solutions to production problems, help with veneering projects, or explore ways to expand their product lines.

Interior designers have used Schürch as a resource to find unusual materials and make their ideas work, a service he would like to expand.

He has run an apprenticeship program, modeled after the one he went through in Europe. It required a one- to four-year commitment and regular tests in all the trades associated with furniture making and repair. There have been 10 graduates. However, he is currently not accepting any new apprentices.

Schürch says he wants to grow the consulting side of his business. He also plans to revisit Europe, and possibly Dubai, where a lot of new innovative work is currently being done. He is also hoping to use the Internet for online classes at some point in the future.

“We are becoming a more digital society. People are much less willing to travel, but are still searching for some form of hands-on education. I can easily imagine a virtual class that could be set up between an instructor and several students throughout the U.S. in real time. All it needs is the Internet, monitor and camera set up at all locations making it come close to a hands-on instruction program, done in the comfort of one’s own shop. The technology is there, and it will only be a question of time before some of this could be implemented.”

Contact: Schürch Woodwork, 731 Bond Ave., Santa Barbara, CA 93103. Tel: 805-965-3821. www.schurchwoodwork.com

This article originally appeared in the April 2009 issue.