Performance Enhancements

Ways to improve the workshop environment include better lighting, attention to heat and humidty levels, and material storage and handling solutions

Doing good work depends on a huge variety of factors including skill levels, available machinery and tools, and the ability to design well. It also depends on getting set up right in the workspace, and that includes environmental considerations such as how well the workspace is lit, the heat and humidity levels, and traffic patterns that include both materials storage and handling. Good work also depends on how well people feel in the workshop, both physically and emotionally. Ergonomics (designing the size, shape and layout of the workspace for maximum efficiency and comfort) can play a significant role in removing or reducing risk and discomfort factors.

Let’s begin with lighting.

There’s an old shop adage that says you should have more light on a project when you’re building it than the customer will have when using it. A large light source is certainly an advantage, especially in the sanding and finishing stages of a project when minor blemishes seem to surface most. But the type of lighting is also important. For example, those final sanded and coated surfaces need to be looked at with a raking light that creates shadows and reveals pits or high points. The color of the light can also make a huge difference, and that is measured in degrees Kelvin (K). Keep in mind that, when discussing light, lower temperatures are warm and higher temperatures are cool.

The light from soft white bulbs (ranging from about 2700K to 3000K – and you’ll find the rating printed on most packages) is anything but white. It’s a warm, yellowish light that mutes our perception and hides flaws. Woodwork created under such light can often appear as less finished or fine under more intense lighting. Cooler bulbs in the 3500K to 4100K range are often described as bright white, but that’s also not true. They are still quite warm. Daylight bulbs usually fall in the 5000K to 6500K range and these most accurately reflect natural daylight. Of course, that depends on the day we use as a baseline. It’s somewhere between clear blue skies and overcast, depending on the bulb manufacturer’s standards. A rule of thumb is that the higher the temperature in Kelvin degrees, the whiter the light becomes. There is a point where a woodshop’s lighting shouldn’t be too white, as this can distort how stains and coatings, or natural wood colors will appear.

This is a good time for woodworkers who are looking to upgrade both task (concentrated light on a single machine or workbench) and ambient (overhead illumination) light fixtures because of the emergence of LED technology. Light emitting diodes (LEDs) are semi-conductors that give off light when an electrical charge passes through them. Think solar panel in reverse. A photovoltaic cell on your roof gathers light and converts it to electricity. An LED does the opposite. They are quite inexpensive to run, last longer and in most applications deliver better lighting. They are easy to focus on a task, and small enough to hang from a ceiling and not interfere with the work.

But before you rush out and replace every light in the shop with new LED fixtures, there is a word of caution here. The American Medical Association has suggested that LED exposure over several decades may increase the risk of developing cataracts, and possibly accelerate age-related macular degeneration. Plus, the fixtures can be a little more spendy than traditional ones, although that’s slowly changing and the lower running costs more than compensate for a slightly higher initial cost.

Heat and humidity

Every woodworker knows that materials respond to changes in moisture levels and temperature. The trick is to find levels that work best for employees as well as solid wood and sheet goods. The challenge is to relate relative humidity (RH) to moisture content (MC).

Relative humidity is the amount of water vapor present in air, expressed as a percentage of the amount needed for saturation at the same temperature. So, if the relative humidity is 72, then the air is holding 72 percent of the amount of water that it could possibly hold.

The warmer the air, the more moisture it can hold. That’s because warm air expands. But when we warm up the shop in winter, we dry out the air and need to add humidity, which seems like a contradiction. The reason is temperature. Cold air occupies a smaller volume so it requires less water to saturate it. Even when the humidity is relatively high in winter, it doesn’t feel sticky. But in summer, especially during a heat wave, the air expands a lot so it takes a lot more moisture to reach the same percentage of humidity, and that’s why it feels uncomfortable and clammy.

Wood is hydroscopic. That is, it absorbs and releases moisture fairly easily. (Bound water in the cell walls is less reactive than free water in the cell void.) That ability to shed or draw in moisture is what makes wood move across the grain. When we kiln dry hardwood, the ideal goal is to release enough water so that the wood neither sheds nor draws when it exits the kiln. For that to be successful, the relative humidity in the shop air needs to match the moisture content in the wood. And ideally, the humidity in the air will remain within a narrow range of change, so that the wood can stabilize and remain stable. With a forced air heating system in northern states, the relative humidity can actually drop below 10 percent in winter. And when summer storms roll in, it can rise to 90 percent. If the woodshop has central air conditioning, it will need a humidifier in winter and a dehumidifier in summer to even out the cycle. That can help prevent warping, checking, shrinking, expansion, problems with waterborne finishes and adhesives, static electric challenges and even dust control.

The bottom line here is that the shop’s geographical location (north, south, coastal or lakeside, elevation, etc.), its heating and cooling systems, its cubic volume (especially interior height), the amount of insulation, passive solar gain and the orientation on the lot can all affect humidity levels. The best course is to talk to a company that makes and/or installs woodshop humidification systems and have them create a plan that moderates and maintains the relative humidity at about 50 percent.

Materials storage and handling

It’s been well documented that a happy worker is a productive worker. People in pain aren’t happy, so a work environment that causes pain is obviously not a great idea. Yet we continue to buy, install and use a huge variety of machines and equipment designed for the average person.

Who is average?

A cabinet shop crew might have somebody who is five-feet tall working next to somebody who is six-foot-three. One team member might be in her 20s while the next is close to retirement. Two people working the same machine may have a hundred pounds difference in their weight.

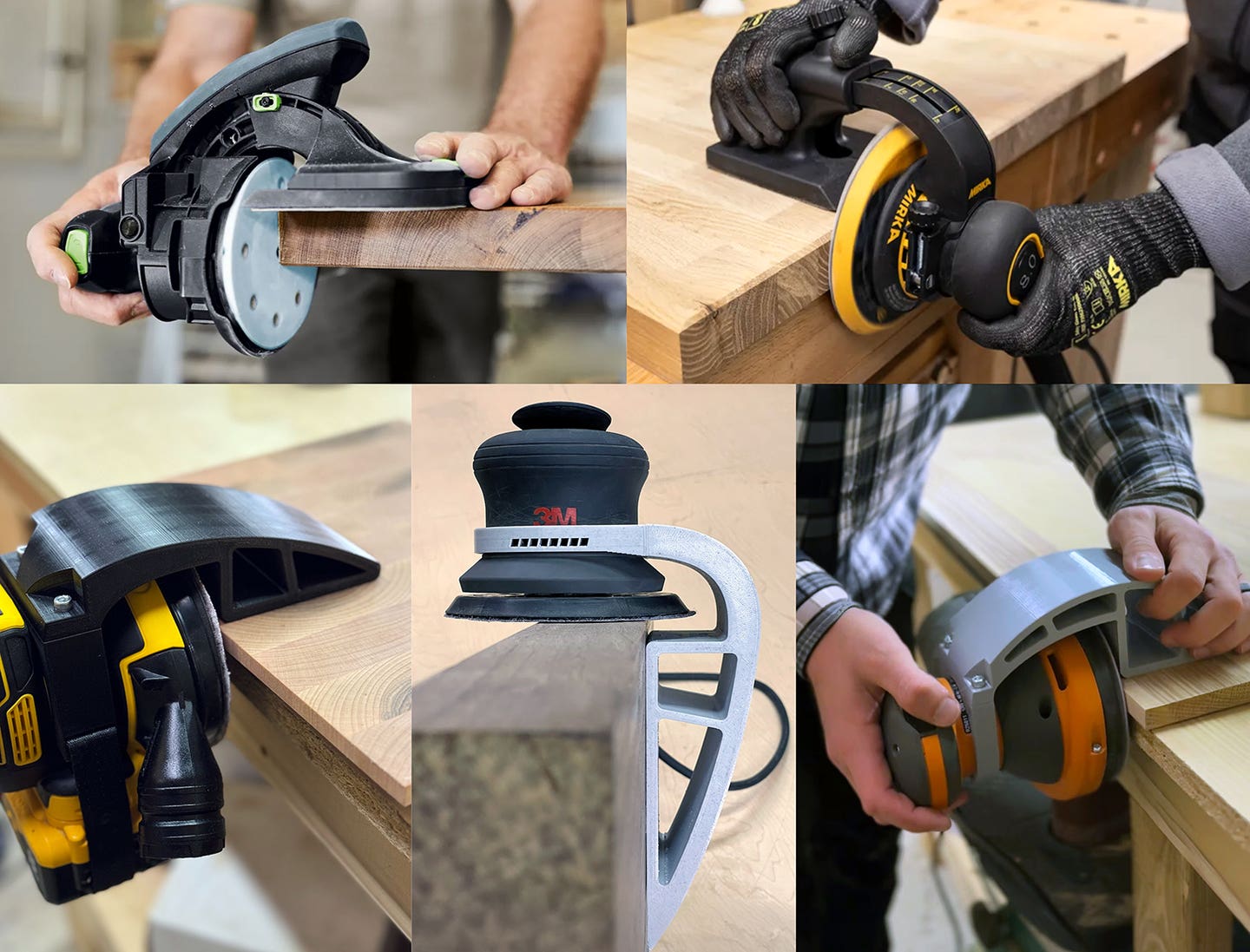

There are workarounds that a woodshop can use to accommodate these differences and save people’s backs and demeanors. There are several companies that produce workbenches with scissor lifts or other devices, where the tabletop height can be changed in a couple of minutes. If it’s a wide workbench, one side can have a small platform on the floor, where shorter employees can stand. Taking that to another level, should there be a low platform around the CNC or table saw if most of the employees are shorter than ‘average’, or perhaps one under the machine if they are taller? Are there two table saws, where one could be modified and the other remains at factory spec?

There are hand carts for moving lumber and plywood around the shop where the base perfectly matches the height of a pallet so product can be slid, rather than lifted to load it. There are carts that are hinged so they swing from vertical to horizontal, and then the height can be changed so that panels can be slipped onto a CNC bed rather than having to hoist them. There are vacuum arms and co-bots (robotic arms) that can do the lifting too, if there’s room in the budget.

Even storage shelves can be adjustable, or at least well enough designed so that materials are easier to extract and load. The idea here is that the first priority should be to store materials for employee health and convenience rather than just in the most efficient way from a shelf space viewpoint. For example, it may be a little easier to pick up and move a sheet of material that is stored vertically rather than horizontally, depending on the cart or machine to which it is headed. And there’s not much sense in putting hardware, connectors, biscuits, screws or even cans of finish where only the tallest employees can easily and safely reach them.

Keeping the crew safe, happy and physically comfortable can certainly enhance performance. Not doing so will most definitely have the opposite effect.

This article originally appeared in the June 2020 issue.